That Satan with less toil, and now with ease

Wafts on the calmer wave by dubious light

And like a weather-beaten Vessel holds

Gladly the Port, though Shrouds and Tackle torn;

Or in the emptier waste, resembling Air,

Weighs his spread wings, at leasure to behold

Farr off th’ Empyreal Heav’n, extended wide

In circuit, undetermind square or round,

With Opal Towrs and Battlements adorn’d

Of living Saphire once his native Seat;

And fast by hanging in a golden Chain

This pendant world, in bigness as a Starr

Of smallest Magnitude close by the Moon.

Thither full fraught with mischievous revenge,

Accurst, and in a cursed hour he hies.(John Milton, Paradise Lost, Book II.1041-55)

William Anders, “Earthrise,” NASA Apollo 8 mission, December 24th, 1968

Repeatedly John Milton’s Paradise Lost describes the world as a small and vulnerable orb, and positions this view from an angelic or devilish gaze: from the eyes of Raphael as he swoops down from Heaven on the way to instruct Adam in the knowledge he should not desire, or from the eyes of Satan as he emerges from the abyssal depths – in Milton’s vaguely heretical schema of the universe – in order to unleash the Chaos beneath the world. And in the first instance of this recurrently swooping, airborne and almost proto-cinematic gaze of the world viewed external to human perspective, Milton’s P.o.V. innovation ties what I want to claim is a profoundly ecological gaze to the view from that void and abyssal Chaos outside the Creation beheld by Satan.

This means that in his purported aim “to justify the ways of God to man,” one of Milton’s principle formal techniques is to sever his reader from what a deep ecologist might call the “life world” in which he/ she is embedded, and force him/ her to look from the impossible aerial verticality of the eyes of an alien being. For Thomas Aquinas, angels do not have bodies, and yet they may chose to assume them, though this places their motion and vision in a displaced relation to their essences. As he writes in the fifty-first question of his Summa Theologiae,”When an angel assumes a body the result is a body that represents its movements.” Doubly exploiting this mimetic displacement, Milton situates his reader up above the world, in the displaced cosmos marked as off-limits by the knowledge Raphael forbids, occupant of a gaze divided from the world and a visuality representative of the ascending conflagration threatened to the world. If, as Helen Gardener has argued, Satan is European literature’s last great hero, part of his depiction, and the dissipation of the possibility of future mimetic heroes rendered in that depiction, is the technical emplacement of the hell-gaze into this poeisis. This means that Satan could never claim, as does the foundational lack of subjectivity aphoristically and mischievously named in Jacques Lacan’s pithy rebus: “You never look at me from where I see you.” Precisely by asking us to look at Satan from where he sees us, from this gaze from the abyssal depths, Milton innovates an impossible and subterranean ecology – and does so at the cost of the hero, whose literary potential he destroys for posterity in this uncanny ecology.

Profoundly of the astronomical age of discovery and scientific revolution in the spherical bodies that comprise our solar system, the era of Copernicus, Galileo and Kepler, and Bruno, Milton lifts his readers didactically up above the world in order that they re-calibrate hierarchical allegiance, shifting from an Absolutism that sustains the elevation of the monarch in the name of God, to underworld gaze onto a radical new politics of liberty.

As Timothy Morton perceptively notes of the iconic image widely know as Earthrise, Milton “would have enjoyed how” the NASA photograph of the Earth appearing from behind the moon, taken by William Anders whilst the Apollo 8 mission was in lunar orbit,

displaces our sense of centrality, making us see ourselves from the outside.

(Timothy Morton, The Ecological Thought, 2010, 24).

As the first colour photograph to capture the Earth from outer space, taken on December 24, 1968, as Wikipedia describes, with a highly modified Hasselblad 500 EL loaded with 70 mm custom Ektachrome film, Earthrise has in the arguments of some, been associated with a global shift in consciousness. By stepping beyond the boundary of home, capturing a blue sphere, this “pendant world” hanging – fragile and “fraught” as Milton has it – in the blackness of space, the NASA astronauts perhaps triggered, or contributed to the momentum of a revolutionary new phase of ecological consciousness. Galen Rowell, for example, has called it “the most influential environmental photograph ever taken.” Certainly in the tumultuous social changes that rocked the mid-late 1960s, the new politics of environmentalism was in the process of going mainstream, following from the publication of what would become classics in the genre, such as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), a powerful yet measured scientific analysis of the overwhelmingly negative impact that modern industrial processes have on the world, in particular focusing on the process of “bioaccumulation,” whereby food chains accumulate hazardously toxic concentrations of agricultural pesticides, such as DDT, widely used in Western agriculture, and discrediting the widespread dissemination of misinformation concerning the safety of toxins by public officials state and the chemical industry. Milton anticipates this threat, and the difficulty of speaking it clearly, by envisioning an uncanny, underworld ecology.

Hell-gate

…on the abyss of the five senses, where a flat sided steep frowns over the present world, I saw a mighty Devil folded in black clouds, hovering on the side of the rock…

(William Blake, “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell”)

The underworld ecology lurks at the precipice of the sensory – the cliff’s edge of the perceptible. It is a fragmenting of the known, a devilishness at the void opened in meaningful organization.

Underworld ecology is not a reaffirming of the Romantic view that Milton was “of the devil’s party” as Blake’s devil famously claims in “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.” Yet the Romantic sense of marriage is vital to the underworld ecology. The hell-gaze of subterranean ecology repeatedly underscores why there is no contradiction between Milton’s fervent Republicanism (for which only his blindness and the intervention of his pal Andy Marvell saved him his life in Restoration England), and the servile mimicry of Republic liberty – and also debased tyranny – by which he sketches Satan’s misery. For Milton’s idiosyncratic version of Puritanism, worldly politics and worldly fragility are a vital component of theology. Satan might rail against the “Tyranny” of the “Thunderer” – by which he refers to his enemy and creator, God – and speak stirringly of the liberty of the mind (rather as Milton dedicated the majority of his writing life to pamphleteering and diplomatizing the Republican cause):

Here at least

We shall be free; th’Almighty has not built

Here for his envy, will not drive us hence.

Here we may reign secure, and in my choice

To reign is worth ambition, though in Hell:

Better to reign in Hell than served in Heaven. (I.258-63)

Yet, this apparent alignment of Satan and Milton’s hero Cromwell, as Stanley Fish has convincingly argued, does not make Milton “of the devil’s party” – whether or not he knew. Rather, precisely the temptation to rally to Satan’s deceptive words are central to Milton’s didactic stylistics. “Intangling” his reader with a heroic and poetic version of Satan – the version Blake and Shelley loved – Milton demonstrates our fallenness, or vulnerability to deception.

And verticality is recurrently central in sketching this stylistics of subterranean politics. Take Satan “High on Throne of Royal State” at the beginning of Book II:

by merit raised

To that bad eminence; and from despair

Thus high uplifted beyond hope, aspires

Beyond thus high, insatiate to persue

Vain war with Heaven. (II.5-10)

The monarchical pomp of “bad eminence” – a height “insatiate”, ever longing for assurance that it is not forever caught in the lowest bowels of Chaos – anticipates the stupidities of Mammon and Beliel, whose sloth and cowardice alike wish to avoid at all costs war with God, in his rousing claim they will make Hell into a Heaven:

The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heaven (I.254-5)

In the delicate and continual promise of deception worked through by Milton’s language, Satan is not lifted above (“from”) despair, but – as is gradually clarified – is rather carried upwards by his despair. A stage later than the fragmentation that Benjamin reads in Baroque allegory, language for the fallen (for all of human history) is a site of deception – a portal by which the underworld comes to the world. Satan’s inabilty not to “persue/ Vain war” also anticipates Moloch’s later “sentence for open war” (II.51). There is no choice for Moloch, as is fully clarified, despite the fact that aim of the war is impossible, because “what could be worse/ Than to dwell here” (II.85-6). Hell is so intolerable that war could not be worse: a far cry from the “secure” place the deceptively fantasist and foolish rhetoric of Satan pictures. So Milton’s reader, if attentive, or “fit” as the blind poet writes, is fully ready for Satan’s own admission that:

Me miserable! which way shall I fly

Infinite wrath, and infinite despair?

Which way I fly is Hell; myself am Hell;

And, in the lowest deep, a lower deep

Still threatening to devour me opens wide,

To which the Hell I suffer seems a Heaven.

(Book 4, lines 73-78)

This hell is a moveable beast – an underworld of the mind – that will follow Satan wherever he goes: an infinite falling that threatens constantly – whenever he is in the lowest deep imaginable, to swallow him into a further the abyssal descent. So that the “High Throne” of his monarchy is one of the many false perspectives suggested by Milton, located in the space and infinite motion of a tragic katabasis from which no end can be envisaged, no recollection or reunion with God possible. And this means that the verticality of the gaze becomes a political tool in Milton’s style, the hell-gaze upwards at the Prince of Darkness from the eyes of the fallen angels in the depths of the underworld parodying and refuting the Absolutist hierarchy that traced a “golden Chain”, in Milton’s words, between monarch and God.

In Milton’s schema of the Creation the Biblical account in Genesis is supplemented by a non-verbal act of preliminary material organization. Prior to God’s speech-action initiation of luminescence, the first divine act described in the canonical account, Milton’s divine geometer compassed the universe, as a sphere shaped in the calm of the “fervid Wheeles” of Chaos:

Then staid the fervid Wheeles, and in his hand

He took the golden Compasses, prepar’d

In Gods Eternal store, to circumscribe

This Universe, and all created things:

One foot he center’d, and the other turn’d

Round through the vast profunditie obscure,

And said, thus farr extend, thus farr thy bounds,

This be thy just Circumference, O World.

Thus God the Heav’n created, thus the Earth,

Matter unform’d and void: Darkness profound

Cover’d th’ Abyss: but on the watrie calme

His brooding wings the Spirit of God outspred,

And vital vertue infus’d, and vital warmth

Throughout the fluid Mass, but downward purg’d

The black tartareous cold Infernal dregs

Adverse to life: then founded, then conglob’s

Like things to like, the rest to several place

Disparted, and between spun out the Air,

And Earth self ballanc’t on her Center hung.Let ther be light, said God. (VII.224-243)

In marking off the universal from the “Matter unform’d” like a colonialist staking territory, God divides off the Abyss from the territory of the Creation. If the Chaos prior to this primal division “heard his voice” (VII.221), following this intervention the sensory capacity of the pliant zone has become “void”: “darkness profound/ Cov’d the Abyss.” So that the creation of the universe also devalued and darkened that which was cut off in establishing the new territory: prior to the light that God orders to the world, he shrouds all the rest in darkness. Like a cinema dimming the lights before the projection (though worked through vertically), “downward purg’d” were the “black… dregs/ Adverse to life.” In Milton’s idiosyncratically kabalistic cosmology, the underworld was cut off from space as God’s aboriginal act.

Thomas N. Orchard, “Milton’s Universe”, 1913

The hell’s eye view is the time of immanent judgement, when all but the few (the few readers, though fit of Milton’s poem) have lost sight of the earths bounded fragility, sustained and enclosed by the darkness of the indifferent universe, open from the beginning to the portals of the underworld and the darkness of night.

Carnal world

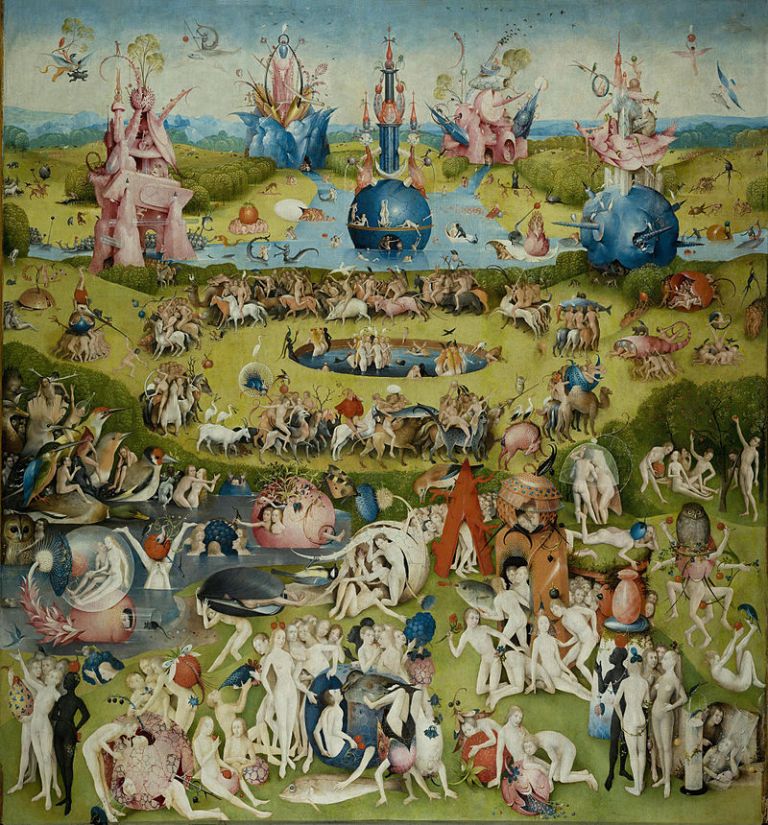

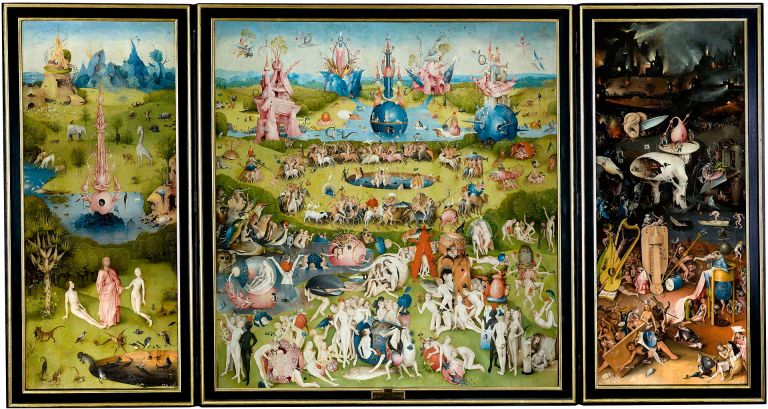

The underworld as the “other” whose formation was necessary to Creation – the negation of life and light by which universal cohesion holds together – and the cracks in language that give passage to hell in Milton’s didactics, should be considered alongside the fantastic style and fetid, fertile and impenetrable imagery of Hieronymous Bosch’s remarkable impasto triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights (1503–1515).

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, Museo del Prado, Madrid

In Bosch’s disconcerting vision, a complex exchange of gazes and dark-holes centres on an eye gazing out of the centre of Paradise. Nicolas Cusanus writes “Lord Thou art an eye,” but looking in Bosch is not the privilege of godliness alone. Echoing Christ’s pious eyeline, as he directs the gaze of the first humans away from the pleasures of Eden, and towards a fetid pool in the corner of Paradise from which slimy, hybrid, dark creatures crawl and consume one another, and also the pouring flock of dark birds as they pour from a dark cave, and loop around to soar through a circular hole in a pendant rock formation in the background of the painting, an owl gazes from a pupil-like darkness at the centre of a iris-like sphere at the bottom of a pink baroque tower at the centre of Eden.

Hieronymous Bosch, The forest that hears and the field that sees, Kupferstichkabinet Berlin, ca. 1500

The cracks in the fragile globe, and in the wanton allegorical depiction of corruption, are raised to a higher power in the third and more explicitly hellish panel. The fragile cracks at the centre of the central panel are perhaps matched in the anal void of the cracked shell that forms the body and the object of the Treeman’s fascination, at the visual centre of the Hell panel (this is an allegory of the artist’s grotesque invention?). For Koerner this means the self is already in Hell: the corrupt fixation on the site of gaze and baseness makes the gaze a decadent recirculation of the corruption:

The Treeman cannot be an object, since it looks, reflexively, back upon itself. But neither can it be a subject, since it cannot face what it seeks to see. What it displays and what it desires is its own absence. It is almost as if Bosch had pondered the meaning of the prefixes “sub-” (“under”) and “ob-” (“against”), and rejecting these, arrived at the visual equivalent of “ab- abject the bottomless entity turned against itself. (Koerner, 94)

Right panel, The Garden of Earthly Delights

If the senses are condemned in this queasy carnality, it involves a horrified condemnation of music alongside recurrent violently penetrated bodies, as if the torture of being is finally located as the piercing income of the senses: hell as the sensory emplacement in the world. The Treeman is filled with other beings, his identity flagged with a pendant image of the organ-shaped pipes he wears as a hat because the self is fragmented, wracked, riven and with alterity. Bosch’s disgust is thus at the unhygenic mess of the sense that renders identity so continually violated, cracked, enamored or enslaved that it must be considered, in the harsh glare of the hell-gaze, as hollow. The carnal world thus undoes itself: where flesh is sole heir to Paradise, flesh is a broken shell.

Being hell: the devil of details

No one sings as purely as those who inhabit the deepest hell – what we take to be the song of angels is their song

(Franz Kafka, letter to Milena Jesenská)

In this sense of a contaminating gaze that delivers hell to the perceiver, we might understand the sense and chronology of the image painted on the hinged outer surfaces of the oak panels that transform the triptych’s side panels into shutters. When Bosch’s hellish Paradise is safely locked away, it is enclosed in an image of the very same fragile orb that NASA termed Earthrise, and Milton, from Satan’s P.o.V., described as the “pendant world.”

Exterior panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights, depicting the creation of the world

This image has been understood conventionally to represent day three of the Genesis Creation, with plants and not animals, or perhaps, especially by Gombrich, as the world after the flood, stripped clear of corrupt and hollow flesh. Perhaps too, in this sense, the opening of the triptych is Bosch’s rendering of God’s omniscient view on time, in which all events are concurrent and co-existent. This is the difficulty that Milton struggles with most: how to get omniscient temporality into an essentially chronological narrative structure, and it renders his God somewhat of a cold-fish in those mind-bending moments of always-not-quite-satisfactory self-explanation (such as his justification of the insignificance of his prior knowledge of the inevitability of the Fall on the guilt that should be attributed to mankind):

…if I foreknew,

Foreknowledge had no influence on their fault,

Which had no less prov’d certain unforeknown.(Book 6, lines 118-120)

The fragile globe in this reading is our view of God’s view – what we would see if we looked from God’s viewpoint. And the opening of the work to reveal the triptych takes us into something more like God’s multi-temporal simultaneity, so that art is an approach to the divine perspective otherwise impossible.

If this reading is sustainable, I think it is entirely reversed in Milton’s vision of Satan’s approach to Eden, the coming together of world and violator that is at the heart of Milton’s narrative structure. For Bosch, coming to the work is a step into the divinely perceived details of the world. Starting from the same fragile world suspended in night, for Milton Satan’s the coming crisis is rather told by combining the distance of God’s cool perception of immanent destruction:

…he wings his way…

Directly towards the new created World,

And Man there plac’t, with purpose to assay

If him by force he can destroy, or worse,

By som false guile pervert; and shall pervert…(Book 6.86-90)

And the drone’s-eye-view of Satan as he cruises over Eden:

With what delight could I have walkt thee round,

If I could joy in aught, sweet interchange

Of Hill, and Vallie, Rivers, Woods and Plaines,

Now Land, now Sea, and Shores with Forrest crownd,

Rocks, Dens, and Caves; but I in none of these

Find place or refuge; and the more I see

Pleasures about me, so much more I feel

Torment within me, as from the hateful siege

Of contraries; all good to me becomes

Bane, and in Heav’n much worse would be my state.

But neither here seek I, no nor in Heav’n

To dwell, unless by maistring Heav’ns Supreame;

Nor hope to be my self less miserable

By what I seek, but others to make such

As I, though thereby worse to me redound:

For onely in destroying I find ease

To my relentless thoughts… (Book 9, 114-30)

Thy self not free, but to thy self enthrall’d.(Book 6, 181).

Underworld ecology, or: giving what you don’t have to someone who doesn’t want it

A journey into the wilderness is the freest, cheapest, most nonprivileged of pleasures. Anyone with two legs and the price of a pair of army surplus combat boots may enter.(Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire)

Roscoe Windfarm, Roscoe Texas

Love, so empty and fanatasmatic, is central to Lacan’s thought because the “Lesnon-dupes err” (The non-tricked err; or: those who end up in real difficulties are the ones too clever to be tricked). Inscribed homonymically as those who are written into the symbolic system, the name of the father (Le nom du pere), Lacan’s pun dissects and ridicules the cynically astute Dunning-Kruger metalanguage of the self-defined “intelligent” subject (such as the ecologist who has relinquished nature?) who fools him/her/itself concerning the mastery by which he/she/it believes he/she/it is able to exercise agency in language.

In tying something vital (ecology) to an ideological faith in the Lacanian/ post-structuralist unseating of the ego, this thought is doomed from the off, like an owl-gaze peering from the centre of Creation. It is also, unfortunately, meagre in terms of its reading of Lacan. It builds, I want to suggest, precisely a non-duped position: Don’t be tricked into loving nature it – and you – don’t exist! writes Morton. But this refusal of love is itself the most deceived and intangled (to borrow Milton’s term) of positions.

Rather than the passionless distance of the technocratic “ecology without Nature”, the God’s-eye view of the world that writes, as Morton does in The Ecological Thought, that we ought to fill wilderness areas with windfarms, as his argument in World Picture 5 details:

You could see turbines as environmental art. Wind chimes play in the wind; some environmental sculptures sway and rock in the breeze. Wind farms have a slightly frightening size and magnificence. One could easily read them as embodying the aesthetics of the sublime (rather than the beautiful). But it’s an ethical sublime, that says, “We humans choose not to use carbon”—a choice visible in gigantic turbines. Perhaps it’s this very visibility of choice that makes wind farms disturbing: visible choice, rather than secret pipes, running under an apparently undisturbed “landscape” (a word for a painting, not actual trees and water)…Ideology is not just in your head. It’s in the shape of a Coke bottle. It’s in the way some things appear “natural” – rolling hills and greenery – as if the Industrial Revolution had never occurred. These fake landscapes are the original greenwashing. What the Scots are saying, in objecting to wind farms, is not “Save the environment!” but “Leave our dreams undisturbed!” World is an aesthetic construct that depends on things like underground oil and gas pipes. A profound political act would be to choose another aesthetic construct, one that doesn’t require smoothness and distance and coolness. (Timothy Morton, “Unsustaining,” http://www.worldpicturejournal.com/WP_5/Morton.html)

You could see turbines as art. You could. You could see global warming as art. Or mass murder – each of which arguably reproduce aspects of the unthinkably sublime more effectively than wind turbines. Smoothness, distance, coolness: these are the “bad” adjectives by which Morton condemns the longing for wilderness. But if I fantasize Abbey monkey-wrenching Roscoe Windfarm, none of these words seem true to that dream-going into the wild (and, come to think of it, surely the “sublime” pleasure that Morton would locate in Roscoe could only ever be distant and cool?). “The ecological thought permits no distance,” Morton continually emphasizes, but it is a closeness like God’s relation to time: embedded in the non-smoothness of all events, yet coolly outside the world. It is an Earthrise painted by Bosch whose doors are locked. “World is an aesthetic construct” in this context means: because any motion, any thought, any love is never empirically more than I, I, I, me, me, my that no place should go untouched. Do we not rather need, like Satan, to get close enough to the mirage Nature to feel our own impossibility? We need to feel pleasure in the impossibility of Nature as did Thoreau, and later, likewise, as did Richard Halliburton, Edward Abbey, Charles Sprawson, Patrick Leigh Fermor, with heavy backpacks and full hearts. We need Nature with ecology precisely because the “the ecological thought” is just another of the “sacred codes” that would lock up the weakest desires, and is powerless to touch the most violent. We need to love Nature as Satan feels love empty himself of substantial being; we need to become hell in our love that cannot be given, and which involves no place tangible or receptive to that (empty) gift. We who have the God-like power to touch everything, need from the fantasmatic underworld love that burns in our hearts, need more than anything in us, that is to say, to let some things and some places remain unsullied and only loved.